ADS-B INERT and ALERT for UAS Revisited

Back in 2018 – we published a white paper titled “Inert and Alert: Intelligent ADS-B for UAS NAS Integration: Concept of Operations.” In it, we described a concept for a way to leverage the undeniable safety benefits of ADS-B for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) without “overwhelming the spectrum” as is oft-repeated when the topic arises. With there being a change or two in the industry since 2018, we thought it was time for a refreshed discussion on the topic.

First, we must address a big assumption head-on.

Surveillance vs. Safety

ADS-B for drones isn’t about surveillance or remote identification – it’s about safety. This is a surprisingly hard concept for some to grasp because – well – it was designed primarily for Air Traffic Control (ATC) surveillance – and the safety benefits of cockpit-to-cockpit traffic awareness were really just a beneficial by-product. So, when you design a surveillance system, there are certain things that fall out as requirements – two very important ones in this context:

- You must see the aircraft all the time. If something “drops off radar” in the ATC world…this is cause for significant concern….so the system you design (ADS-B) needs to be “always-on”. The FAA addressed this in 14 CFR 91.225(f) by requiring the ADS-B system on aircraft to be always in transmit mode, even if you aren’t flying in mandated airspace unless you fall into an exemption category.

- You must see the aircraft from very far away. To minimize the cost of the ground network, it isn’t nearly as dense as a cell tower network, and the closest tower may be 50-100NM away or more. This translates to some pretty high-power transmitters on the aircraft flying around to reach those ranges.

Summing up the two items above results in lots of high-power transmitters flying around transmitting all the time, which quickly translates to lots of spectrum utilization.

But we don’t want to “control” most drones using ATC like we do for manned aircraft. That’s what the entire Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) initiative is about. So, we can completely remove the “surveillance” use-case of ADS-B for UAS, and wow – this becomes a revolution. We are suddenly free of the high transmit power and always-on handcuffs (because UAS fall into the always-on exemption thanks to the new remote identification rules) that would have been the very cause of “overwhelming the spectrum” that everyone is so worried about.

This is where Inert and Alert comes in.

Quick Inert and Alert (I&A) Refresh

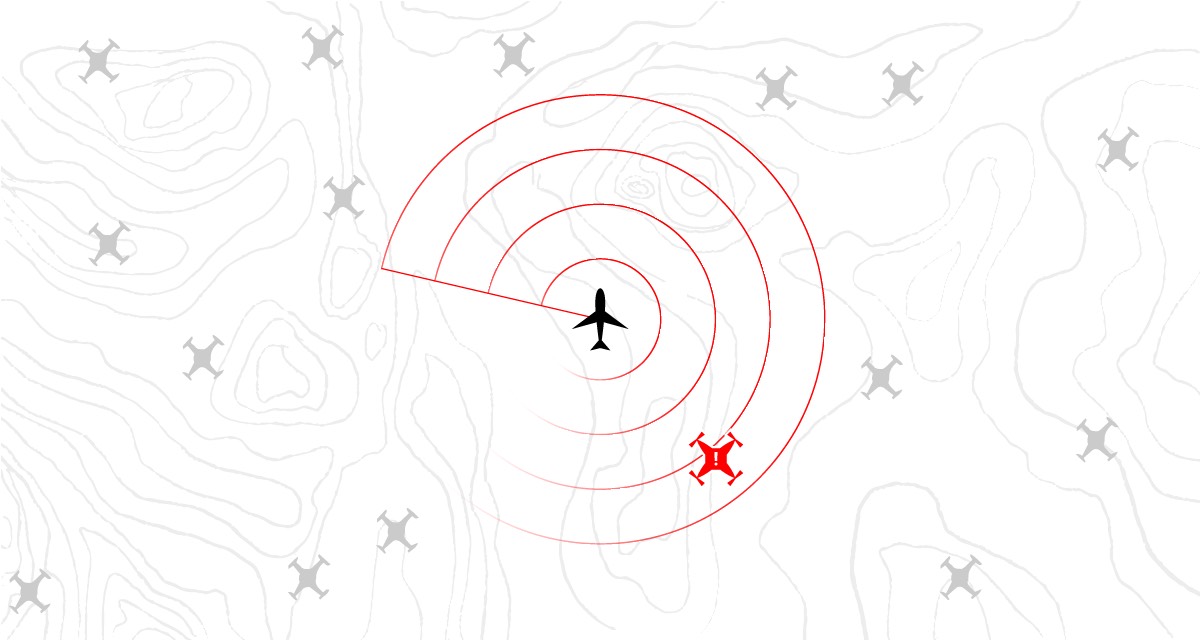

Let’s start with what I&A is not. It’s not a surveillance system. It’s not transmitting all the time. In fact, in most cases, it will never transmit at all. It’s not high power – it can be as low as 0.1W yielding a range of just 1-2 miles (exceeding most definitions of “Well Clear”). It’s not assigned a unique ICAO address tied to the airframe (a limited commodity), and very importantly – it’s not remote identification. I would also go so far as to say that it likely should not operate on 1090Mhz, the most crowded of the two ADS-B frequencies – although technically it could and perhaps may be a good choice for non-U.S. use. It should use 978MHz in the U.S. as this frequency is radically underutilized as compared to the original ADS-B projections.

What is I&A then? Think of it like a car horn. It is a mostly dormant system that conditionally transmits only in the event of a safety issue, and then stops transmitting when the issue has cleared. So, what is a “safety issue?” Well, we can be flexible in defining that here, but are a few of our thoughts are:

- A lost link scenario where positive control by the operator is compromised.

- With the use of an integrated ADS-B IN receiver, the I&A device detects that a manned aircraft cannot stay “well clear” of a collision. This doesn’t relieve the detect and avoid (DAA) responsibility of the UAS but contributes to airspace awareness and at least allows the option for the manned aircraft to self-separate.

- Geofence scenarios – perhaps the UAS diverts from its UTM flight plan into a Temporary Flight Restriction (TFR), controlled airspace, or military airspace.

These aren’t rocket science scenarios – they can be easily demonstrated, modified, tested again until we get the parameters just right.

Let’s go back now and address some of the few remaining arguments.

Argument 1: The FAA doesn’t want it, not now – not ever.

There is some evidence to the contrary. What the FAA doesn’t want is ADS-B to be used as a UAS surveillance system, as remote identification, or generally under 400’. Here are a few examples though that show there are some legitimate use cases – even for surveillance usage.

- The FAA’s Upper Class E Concept of Operation describes how airspace will be managed above FL600 – where – aside from supersonic and military aircraft – many of these systems will be unmanned. This document describes a blend of traditional surveillance technologies including ADS-B with UTM concepts which the document calls ETM.

- The FAA’s Urban Air Mobility Concept of Operation also describes a similar concept of a blend of traditional surveillance technologies (including ADS-B) with UTM-like systems called a Provider of Services for UAM (PSU). This will increase in importance in the future as low-altitude UAS and eVTOL UAM/AAM platforms begin to crowd the lower altitudes.

- RTCA DO-260C is the latest revision to the standards for 1090MHz ADS-B. Published only in Dec 2020 by SC-186– revisions include new message types for UAS operations, including what it calls “contingency messages” for lost link scenarios. Revisions to DO-282B are currently being made in which similar message types are being incorporated into the 978MHz Universal Access Transceiver (UAT) ADS-B messages.

- The updated 14 CFR 91.225 adds paragraph (i) which requires the use of compliant ADS-B systems if operating under a flight plan and in communication with ATC. It also basically restricts to the use of ADS-B to these types of operations.

- Large military UAS regularly use ADS-B OUT to fly in civil airspace – including the MQ-9/RQ and MQ-4. Indeed, ADS-B is required to fly in Class A airspace without a chase aircraft.

Argument 2: There aren’t enough unique ICAO addresses for drones.

We don’t need unique ICAO addresses for I&A systems. We only need those if we are designing a surveillance system. As a manned pilot, you don’t need to know the tail number of the aircraft you’re about to crash into in the heat of the moment…. only that there is an aircraft there at all. Besides, remote identification provides us with that unique digital license plate, right?

The alternative to unique ICAO addresses is the “Self-Assigned Temporary” ICAO address…and this isn’t something that we made up – it comes again from RTCA in DO-282B. The document provides an algorithm to generate an on-demand ICAO address using seed values such as lat/lon and time of day to generate a random ICAO which the document states “the probability of two aircraft in the same operational area having identical values should be well below the observed probability of having duplicate ICAO 24-bit addresses owing to installation errors.”

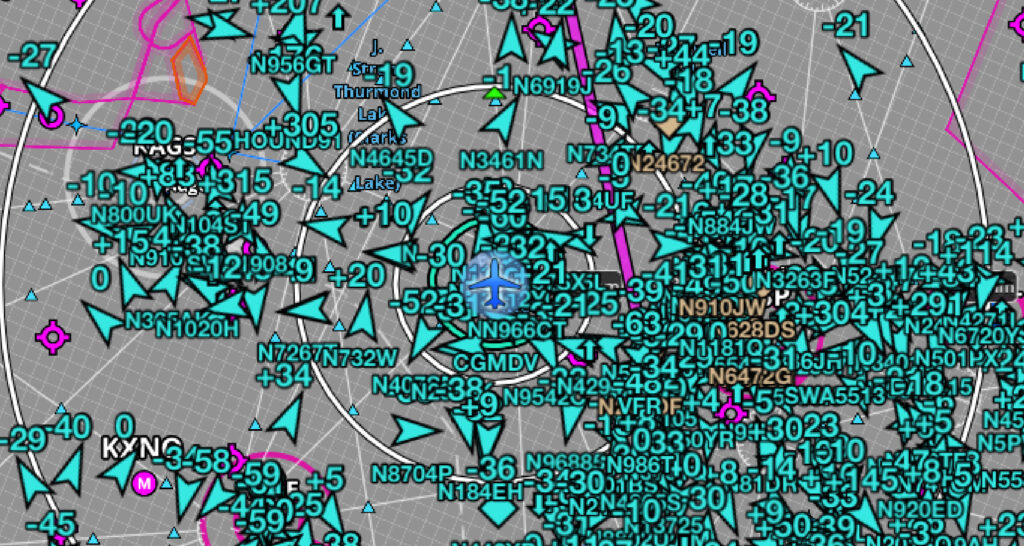

Argument 3: Pilot or Controller overload due to too many “dots” on the screen.

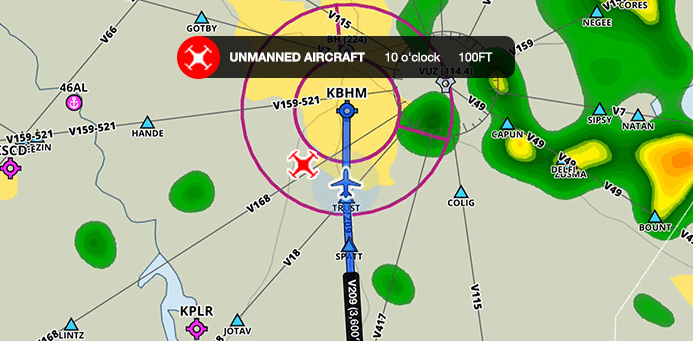

Remember an I&A system will only transmit if a safety-compromising scenario arises, and when it does – it will be at extremely low power. So, if it does appear on the screen – the threat is close to you– and you definitely want to pay attention to that dot on your screen. Additionally, most Electronic Flight Bags (EFBs) and ATC automation displays have altitude filters that ensure you only see relevant traffic anyway.

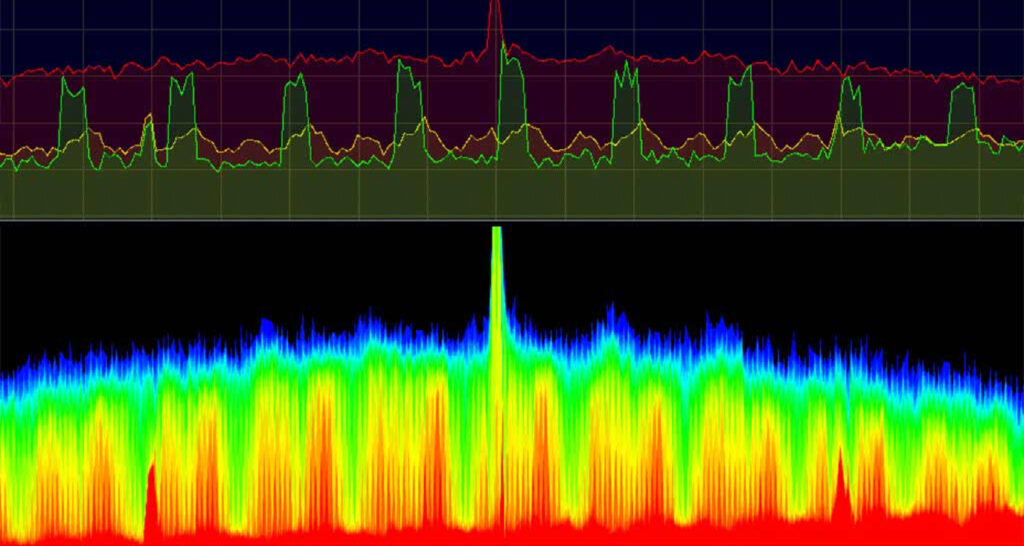

Argument 4: Is there still a spectrum congestion problem?

There are two relevant published studies which are often referenced, but only in the context that they state that they describe the “overwhelming the spectrum” scenario. Let’s take a closer look though.

The first is a MITRE study titled “ADS-B Surveillance System Performance with Small UAS at Low Altitudes”. This study analyzed the impacts of densities up to 14,000 sUAS within a 16NM radius transmitting ADS-B at different power levels as low as 0.05W on 978MHz UAT. Here’s the first paragraph of the conclusion – which describes the opposite of the “overwhelming” scenario:

“The study extended prior research and examined a multitude of scenarios from low to high stress cases. The analysis indicates the key parameters are SUAS ADS-B transmission power and SUAS traffic density. These two parameters can be balanced to attain an acceptable demand on the UAT in areas of potentially high SUAS concentration while still providing safety and utility to all aircraft.”

The second is a EUROCONTROL study titled “Impact of SUAS ADS-B on 1090MHz”. This study used a 20% plus up of a peak date at Charles de Gaulle and Frankfurt airports and studied the impact of a number of scenarios using ADS-B 1090MHz output power at 0.1W and 1W. The conclusion slide from this study indicates that “The impact of SUAS with ADS-B output power limited to 0.1W on the aircraft detection range would be acceptable.” The 1W transmission did show some degradation.

The first study models a fairly “aggressive” density scenario, and the second a bit more reasonable. Neither study describes a doomsday scenario, and these scenarios are modeled with continuous transmission, not I&A conditional transmissions. Returning to the car horn analogy, it would get pretty loud if everyone used theirs all the time, but that isn’t what they are designed for. Beep beep, look out buddy. To us, saying you can’t have I&A on a drone is like saying you can’t have a horn on a car.

Wrapping Up and What’s Next

Despite all of the “thou shalt not ADS-B” in the remote identification rules, the existing FAA rules do support an I&A system. The rules within 14 CFR 91.227 and 91.225 (a.k.a. “The ADS-B Mandate”) are applicable to aircraft which are meant to gain access to controlled airspace and operate under ATC services. In other words – for surveillance purposes. An I&A system in contrast isn’t meant for surveillance – it’s a safety system. The updates to 91.225 from the remote identification rule allow for an exemption of a UAS to not be “always on” – opening the door to a conditional transmission of ADS-B. This definitely opens the door for UAS operating under a flight plan, type certified UAS that will routinely operate beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) and UAS that need I&A to operate safely in a designed area (the National Capitol Region, Class B or C airspace). But, particularly with the advent of passenger carrying UAM UAS that must frequently operate below 400 ft for takeoff and landing, all types of UAS could participate in a I&A system without overwhelming the spectrum.

What DOES need to happen is that the FCC, with the FAA’s approval – needs to be able to issue a license for a low power system that does not meet the power levels required for TSOs or 91.227.

So, we could do this today with a medium power UAT system (the same as a ping2020i, skyBeacon or tailBeacon), but to really be effective in conserving the spectrum utilization, we need to get to approval for 0.1W-1W. I’d certainly feel a lot safer commuting in my UAM if I knew it could detect – and then avoid – all the UAS along the flight route, wouldn’t you?

Christian Ramsey

President, uAvionix Corporation