The Cloud in the Clouds

On a chilly morning in April 2021 on a country road in North Dakota – a group of engineers, pilots, and observers from the Northern Plains UAS Test Site (NP UAS TS) gathered outside of the uAvionix Ground Control Station (GCS) van and watched a matte gray Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) jump to life, vertically ascend to 100m Above Ground Level (AGL), transition to forward flight, bank and turn south on autopilot, and head to a waypoint about 8 miles away. Meanwhile, the pilot in charge (PIC) and Visual Observers (VOs), packed into a rental car, pursued it down a nearby road.

The GCS van incorporated an elevated uAvionix skyStation Ground Radio System (GRS), and another GRS was stationed at the Southern waypoint. Both were connected to the uAvionix SkyLine service layer residing in “the cloud,” where even more engineers were monitoring the flight from all over the U.S.

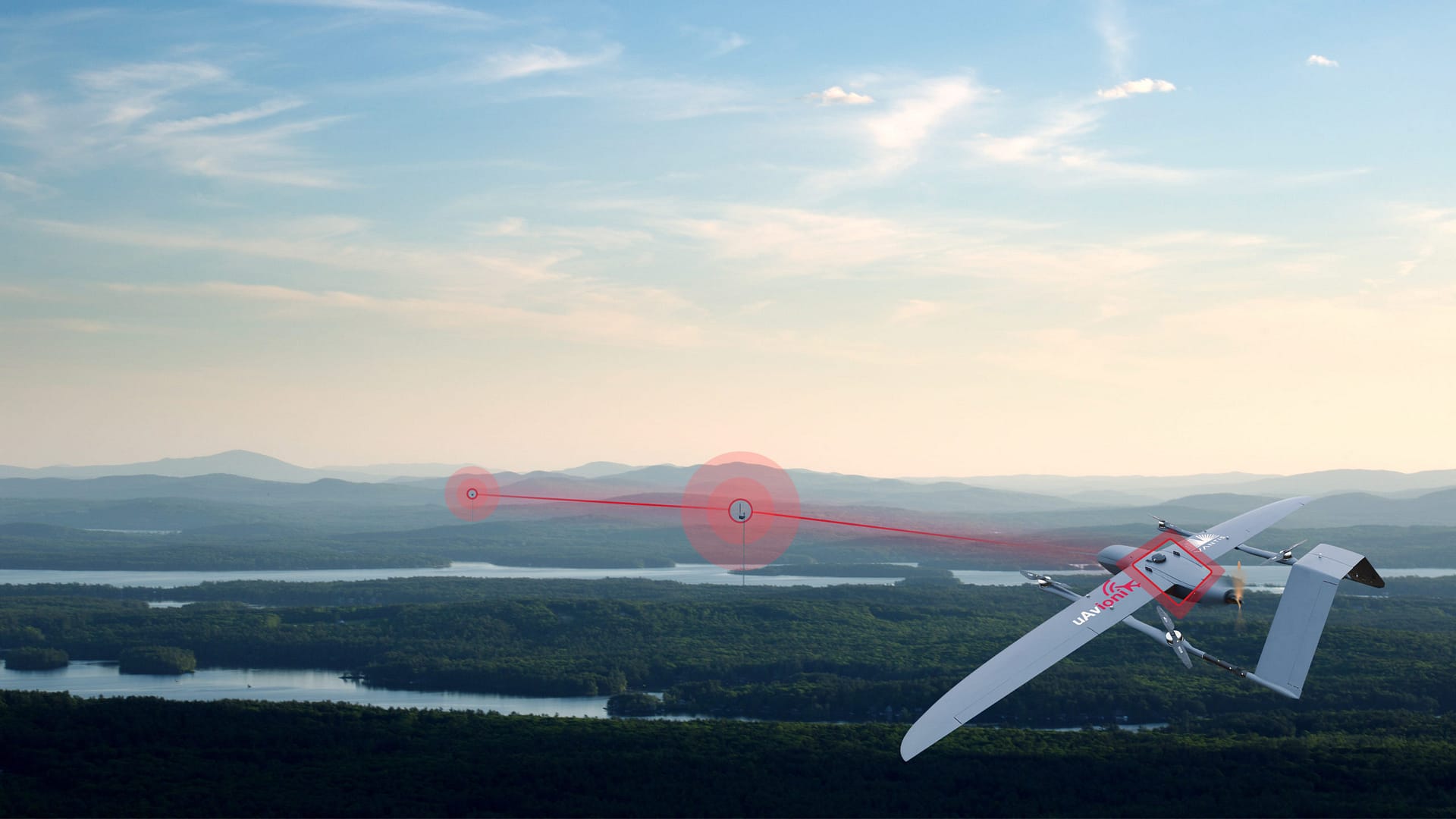

As the aircraft autonomously flew away from the GCS van, the “link quality” of the Command and Control (C2) signal from the uAvionix microLink Airborne Radio System (ARS) controlling the flight diminished as the distance increased between the aircraft and GRS in the GCS. Concurrently, the link quality associated with the Southern GRS steadily improved as the aircraft grew closer. At a point just past the halfway mark, the SkyLine service layer determined that the Southern GRS ahead was the better choice for maintaining aircraft control based on link quality – and in the most anti-climactic fashion ever –simply handed over control to the Southern GRS. If you blinked, you missed it.

Safety gets built-in

So why open this article with a descriptive story of what at first glance appears to be a ho-hum event? Because good safety results in “boring.” If every time you boarded an A320 on a business trip you had to endure a white-knuckle seat-of-the-pilot’s-pants landing – the news might be filled will a lot more “incidents” and there would be a lot less air travel. Don’t get me wrong, aviation is a thrill to be a part of for us enthusiasts, but to most of the population – boring is just fine, thank you. That’s what makes aviation the safest form of travel in the world.

So why open this article with a descriptive story of what at first glance appears to be a ho-hum event? Because good safety results in “boring.” If every time you boarded an A320 on a business trip you had to endure a white-knuckle seat-of-the-pilot’s-pants landing – the news might be filled will a lot more “incidents” and there would be a lot less air travel. Don’t get me wrong, aviation is a thrill to be a part of for us enthusiasts, but to most of the population – boring is just fine, thank you. That’s what makes aviation the safest form of travel in the world.

One reason aviation is so safe is because the entire industry is based on technology purpose-built with safety in mind. You don’t use county roads as runways simply because they’re already there. Likewise, you don’t use the fuel pump from your riding lawnmower in your Piper Cub.

The C2 system is the lifeline of a UAS operation, so, logically, a purpose-built C2 system designed for safety should be the norm. Sadly, it is not, at least not yet. Currently, the UAS C2 landscape is filled with hobby-grade equipment, unlicensed frequencies, point-to-point systems that won’t scale, and re-purposed consumer cellular networks. Read our recent article “A Radio Isn’t a Radio” for some insight into why these things matter, and what can go wrong if a wrong choice is made.

So, what’s the right choice? The entire C2 system needs to be managed as a vertically integrated service that dynamically manages its resources in real-time. To do so it must leverage an architecture that can meet a safety case while obfuscating the details of the underlying transactions from users of the system. What a mouthful! Mobile networks accomplish this for consumers every minute of every day, but those networks aren’t built with safety-of-life applications in mind. Something equivalent must evolve into existence to serve a similar purpose for UAS, but this time with an emphasis on C2 reliability that underlies safety.

A new era of aviation requires a new era of communications. Meet SkyLine

SkyLine is the world’s first certifiable C2 network that’s targeted specifically for UAS and Advanced Air Mobility (AAM). Built on a foundational core of certified and certifiable avionics hardware, SkyLine possesses a network service layer that autonomously monitors the entire network infrastructure and routes a C2 message to its designated aircraft after choosing the most appropriate GRS based on link quality, flight plan, and the infrastructure needs of other aircraft sharing the network.

At its core, SkyLine is a set of network services that can be deployed in a public cloud, private cloud, or local server(s). It manages communications, capacity, handoffs, health and status data, and expansion for the entire ARS/GRS infrastructure.

At its core, SkyLine is a set of network services that can be deployed in a public cloud, private cloud, or local server(s). It manages communications, capacity, handoffs, health and status data, and expansion for the entire ARS/GRS infrastructure.

In UAS operations, two critical aspects of maintaining safety involve the communication links to the aircraft and autonomy. Often, the “autonomy” component is thought only to deal with how the aircraft behaves when the communication links fail. But with SkyLine, it also means managing the communications to optimize safety, capacity, and efficiency of the airspace – to make sure those communication links don’t fail in the first place, but the system responds appropriately when they do.

In terms of scalability, challenges come to light when multiple GRS are required to implement BVLOS flights that extend beyond Radio Line of Sight (RLOS) of a single GRS. Depending on the altitude of the operation, this C2 network architecture may be required for linear infrastructure inspection, transit corridors, or for wide-area volumetric coverage. In these instances, individual certification of the GRS and ARS is not enough to ensure safe operation. Coordinated management of the underlying system as a whole is necessary to ensure safe hand-off from one GRS to the next, overall system capacity is managed, and dynamic spectrum allocations are centrally managed and served to individual radios on a flight-by-flight basis (if not more granularly). This becomes quite complex rather quickly.

The SkyLine managed C2 service is currently deployed as a component of the Vantis UAS BVLOS Network in North Dakota. Future deployments include the New Mexico State University FAA UAS Test Site, and as a part of BVLOS trials in Alberta, Canada with partner Airmarket. Additional undisclosed locations are expected to be announced in the coming weeks.

The Future – Protected Spectrum

The roadmap for SkyLine deployment is intended to both pace and accelerate the industry and regulatory environment. By necessity, initial implementations of SkyLine leverage the uAvionix microLink ARS and skyStation GRS hardware, operating in unlicensed ISM 902-928MHz frequencies. But for more critical and risky operations, the world is moving to “protected spectrum.” And not just any protected spectrum, but “aviation-protected spectrum.” Protected spectrum means significant legal protections are in place to guard against interference at those frequencies. “Aviation” protected spectrum means aviation regulators (FAA, CAAs) are the gatekeepers for who gets to build a radio to access that spectrum. For example, a section of C-band between 5030 and 5091MHz is one such aviation-protected spectral band designated for C2 use. Leveraging these designated bands is how we arrive at a purpose-built C2 network with safety designed in from the outset.

The underlying management services layer is frequency agnostic. This allows future protected spectrum SkyLink “C Band” radios to be “plug and play” with the in-place architecture and provides end-users with the option to switch between unlicensed ISM radios, and licensed and certified C-Band radios.

Dynamic Spectrum Frequency Asset Management

There is still another problem to overcome. RTCA DO-362 describes it as follows (Note “CNPC” means “Control and Non-Payload Communications” and is synonymous with “C2” here. “UA” is an acronym for “Unmanned Aircraft.”):

There is only a small amount of RF Spectrum available for a CNPC Link compared with the expected number of UA that it will need to support. Therefore, the CNPC Link Assignment Scheme must be Dynamic in nature. It must only assign a channel for a short amount of time to any particular UA so that other UAs can use the same channel as soon as it is no longer needed. A CNPC Link assignment will have great value to UAS operators because it is necessary in order to operate. [Appendix I, section I.1]

The roadmap for SkyLine includes the development of a dynamic Frequency Asset Manager (FAM). microLink and SkyLink radios are already architected to accept dynamic frequency assignments to enable the industry to scale at the needed pace.

Back to that road in North Dakota

Returning back from its journey, the UAS – having experienced several more GRS handoffs – transitions back to vertical flight and settles softly down into the still brown grass. Everyone fist-bumps, takes photos, and begins to pack up, eager to head to the Blue Moose for lunch and beverages. It truly is an event worth celebrating. The National Airspace System (NAS) of today combines the airspace, navigation facilities, and communications infrastructure that keeps people and goods moving freely and safely. What uAvionix revealed in that blustery field was the first cornerstone of the next generation NAS.